Described as ‘a satirical literary thriller that’s enjoyable and uncomfortable in equal measure’ by The New York Times, Asian American author Rebecca F Kuang’s Yellowface has generated a fair amount of critical discussion around race, diversity and who gets to tell a story.

Yellowface is told from the perspective of June Hayward, a ‘basic white girl’ who has always felt as if she has had the short end of the stick compared to her friend Athena Liu – the literary world’s new bae who checks all the right boxes for racial diversity, talent and charisma. With Liu’s career cut short by an unfortunate death, Hayward is left with her unfinished manuscript aware it is bound to be the next bestseller.

Through Hayward’s journey of developing, and finally claiming, the story as her own, Kuang’s blueprint for Yellowface is laid bare. Ethical and moral considerations aside, it’s not hard to relate to the bitterness and envy that Hayward feels towards Liu’s success, especially when it’s posed with the unbearable optimism of “It happened to me, maybe it’ll happen to you too!” (this writer’s words not Liu’s or Kuang’s).

In this article:

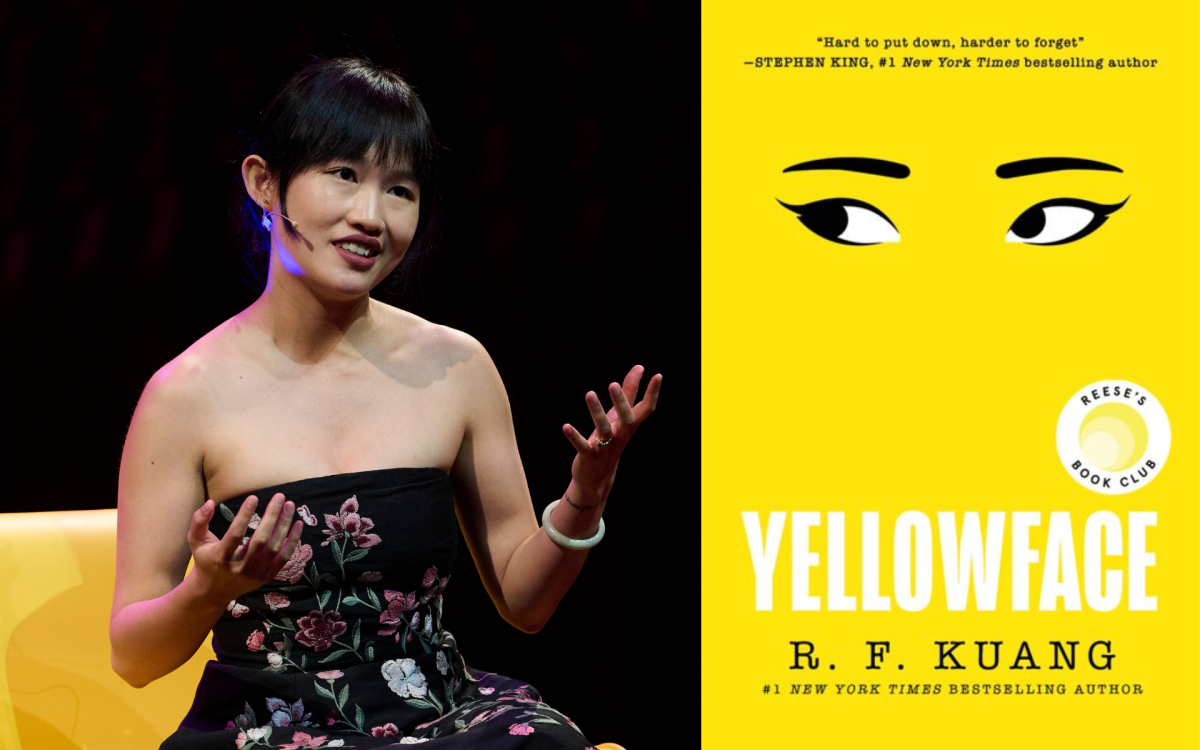

Speaking recently at the Sydney Opera House as part of the All About Women festival 2024, Kuang said the decision to write from the first person perspective of a white woman – one that is petty, insecure and sometimes annoying even to readers – is part of the bigger picture. ‘I was fascinated with the female protagonist who has a voice that is so nasty; she’s judgmental, she’s cool, she’s selfish. She really sounds like the last person that you would go out to happy-hour drinks with, but this voice is so common [in literature] because we’re drawn to it.’

Drawing on the work of cultural theorist Sianne Ngai, Kuang suggested that, instead of focusing on Hayward’s flawed personality, we should be questioning ‘why the person is envious and what sort of power imbalances this speaks to’. She continued, ‘This brings us back to the question of the nasty woman who is criticising everybody and everything, but what is she actually mad about? I think she doesn’t actually hate all other women, but she hates the roles that everybody is forced to perform and she hates that hypocrisy.

’I tried to include some of that in how I wrote June. She’s a hypocrite and, yes, she’s a flaming racist, but she has this impatience for the hypocrisy and performance of everybody else, and that’s why we like her nastiness.’

Identity, cultural gatekeeping and the diversity paradox

In Yellowface, Hayward is driven by the belief that Liu’s success can be attributed to the increasingly “woke” publishing industry and its “diversity quota”. After stealing Liu’s manuscript, Hayward publishes the book under the culturally suggestive pseudonym, Juniper Song. Hayward’s wrongdoing lies not only in the theft of intellectual property, but also of an identity.

Yet, different to what one may expect, it’s not Kuang’s intention to put people in their right place in terms of who can tell which stories. She said, ‘I am pretty much an extremist on freedom for artists. I think almost anything goes and I have this position because I really am sceptical, cautious and quite nervous about work that puts permissions on what you can write from the outset.

‘After a work is published, people will have the freedom to critique your work however they like and you will live or die by the sword of the market. But when we begin conversations with “You never should have written this in the first place” or “You don’t have the right identity, you don’t have the right qualifications, you’re not X, Y, Z enough”, I find that incredibly dangerous, because then we start appointing cultural gatekeepers for making these decisions and nobody’s qualified to make those calls.’

Kuang continued, ‘I am especially suspicious of language like “Stand in your own lane” or “Don’t write about experiences that you don’t have” etc when it comes to race and ethnicity, and what writers of colour are allowed to do – because, more often than not, it backfires. Instead of opening up our opportunities, it just pigeonholes us into the same kind of ethnic trauma trope novel, which Amy Tan did very well, but I don’t think I’m interested in doing in the future.’

Instead of these discussions, the better questions to ask from Kuang’s perspective are “What is the text doing?”, “Why did the author choose to write about these people?” and then in the context of the literary economy, “Who’s getting paid to tell these stories?”.

The idea that diverse or intersectional identities are giving people an unfair advantage is also a paradox, and speaks to racial history and hierarchies of power. Going back to the character of Hayward, Kuang added, ‘June sometimes comes off as ignorant, but she knows exactly what she’s doing. She understands very precisely the dynamics of power and cultural capital in every situation she’s in, and she’s thinking about how to use that to her advantage. In general, I think whiteness and racism has a lot less to do with feigned ignorance and more about a move that is so calculated and habitual that it becomes unconscious – it’s this move to accrue political, material and cultural capital to oneself.’

What does ‘Yellowface’ say about the publishing industry?

So what is Yellowface actually trying to reveal about the publishing industry? Perhaps that, despite these efforts to be diverse and inclusive at the surface level, nothing much has changed?

Kuang said, ‘If you look at all the industry reports in the last few years and, really, dating back to when we’ve had reliable data about the kinds of books that are published, you know that it is overwhelmingly in your favour to be white.

’In this industry, the percentage of non-white authors who are publishing books with the big five publishers has barely budged in the last few decades… Yet, there’s this pervasive myth that it’s impossible to be published if you’re white anymore, that everybody only cares about diversity, that you have to be ethnic or queer or have some interesting traumatic background in order to get your foot in the door.’

Read: Does the publishing industry glorify bright young things?

Kuang traced this myth back to virtue signalling and advertised opportunities that specify diversity as an “eligibility”.

She continued that this has led to the false sense of competition based on identity, rather than actually an indication of someone’s ability to write a good story.

Another reason Kuang chose to write from the perspective of a white protagonist is that ‘it no longer makes it a neutral, default subject position’, but, instead, one that demands to be interrogated.

Is there a role for writers in cultural change?

When All About Women moderator Nakkiah Lui asked Kuang about ‘the role of a storyteller and speaking to cultural change’, Kuang responded, ‘I’m actually sceptical of arguments that authors [are] representatives of an entire culture or having some kind of agenda, because this often leads to bad literature.

‘I have had to read quite a lot of socialist propaganda novels from the 1950s for my qualifying exams, so I know when you go in with the goal of effecting cultural change and you only write to hammer a point over and over again, the craft is not going to be good.

‘I think the artist’s goal is just to tell a good story and to pursue truth in whatever way we define it. When I write a novel, I’m not thinking “I want to convince everybody of this”. I’m just thinking that I want to pick up a rock and the rock is whatever cluster of questions I find really interesting. With Yellowface, it’s race, jealousy and the literary economy… To simplify it as “novelists are our cultural educators”, I think really does a disservice to our craft.’

Rebecca F Kuang spoke at All About Women 2024 on 10 March, the talk was moderated by Nakkiah Lui and is available for rent on Stream – Sydney Opera House.

ArtsHub attended the livestream.