While the concept of community engagement is hardly new, forward-thinking performing arts organisations are embracing and formalising the concept in new and expansive ways.

Increasingly, public breakdowns in trust and communication between artists and arts organisations are illustrating the importance of creating a workplace culture that is genuinely inclusive, safe and communicative. In an industry where development and ticket sales are predicated on connection, reputation and community, internal and external community engagement should be recognised as business critical work – and treated as such. The cost of hiring a community engagement consultant on a production or development, and setting them up to succeed with adequate time, access and remuneration, is not a dispensable budget line.

Indeed, the December survey report from the Australian company, Arts On Tour, A Changing Touring Landscape, found that when ‘rating what’s important in a touring project, 92% of respondents ranked a high level of community engagement number one, followed by a focus on relationship-building and reciprocity’.

Similarly, Arts Council England has named ‘Inclusivity and Relevance’ as one of four Investment Principles in its 2020-2030 Strategy. This means that organisations seeking funding must demonstrate how they are ‘listening to the voices of the public’ and ‘[reflecting] and [building] a relationship with their communities’.

Increasingly, if you look, you will see community engagement specialists credited in programs, consultants listed on company websites and community engagement strategies embedded in presenter pitches. ‘There definitely has been a shift … there is a new urgency,’ observes Sydney Opera House Community Engagement Manager Wanyika Mshila. ‘Audiences came out of [COVID-19 lockdowns] very savvy. People want to be excited a bit more. It is no longer enough to do formulaic cookie cutter work.’

In this article:

‘Community engagement’ versus ‘audience development’

Generally speaking, arts organisations employ community engagement consultants to advise on best practice and shape strategies on topics including onboarding, casting, training, board recruitment and dispute resolution. In practice, the implementation of a community engagement strategy could involve organising focus groups, running cultural awareness and cultural safety training for cast and creatives, facilitating observerships and work experience for emerging artists, measuring community impact, regular reporting and data collection, and even encouraging reviewers of colour to review shows by and for people of colour.

For example, a number of recent productions at the Sydney-based company, Darlinghurst Theatre Company (this writer’s former workplace) featured successful complementary events like the Trans Theatre Symposium alongside Overflow and a roving library during seven methods of killing kylie jenner.

Read: Australian-UK collaborations driving artistic exchange and innovation

In many ways, it is easiest to define community engagement in terms of what it is not. It is not short-term, reactive or a public-facing ‘scramble towards superficial diversity’. In the words of Angela Davis, ‘Diversity is a corporate strategy … it’s a difference that doesn’t make a difference’.

Meaningful engagement is sustained, intentional and self-reflexive. Funding, trade-offs, compromises and time are required. Instead of spending thousands of pounds on a one-off speaker fee, for example, a donor could fund an entire community program in an organisation’s backyard. ‘It will mean your cast want to be there, your customers will want to be there,’ advises Pride in Diversity Relationship Manager, Chloe Bonnar. The result ‘is better than a brand; it’s a reputation’.

For Bonnar, it all comes down to connection. ‘If you are living, working and breathing in a space with a community of people, then you need to understand that community and invite them in.’ Similarly, in Mshila’s eyes, the goal of community engagement is to connect with intersectional audiences and, by extension, unpack barriers to attendance and community sentiments.

In contrast, audience development is focused on building a new audience base – which could include historically excluded audience members – through practical initiatives like discounted and complimentary tickets, front of house staff training and foyer activations. ‘It’s completely fine to do audience development,’ says Mshila. ‘But you need to recognise that it is different from community engagement.’

Read: What I’ve learned creating a Cultural Safety Document

Case studies

Sole traders and small companies – Cessalee Stovall, CEO and Founder of Stage A Change

Founded by Stovall in 2017, Stage A Change is leading the sector through its Three Spoke Plan: Artist Training, Community Engagement and Industry Standards. Structurally, the company has shifted from a sole trader model to a social enterprise and not-for-profit, run by a recently announced board of directors.

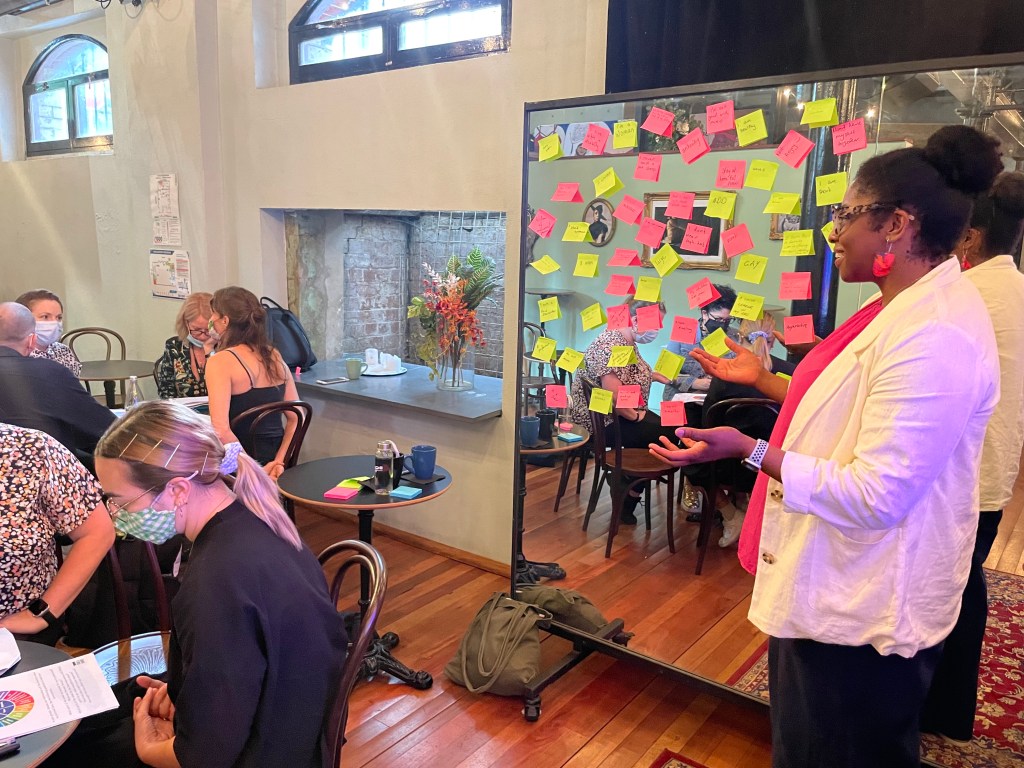

Stovall and her team of facilitators offer a range of consulting services specifically designed for the arts industry. Through strategy development, interactive learning labs, industry roundtables, artist training programs and casting support, Stage A Change creates new opportunities for aspiring artists of colour throughout Australia, and empowers arts practitioners and theatre companies to be changemakers in the sector, facilitating tough conversations with its ABIDE framework for access, belonging, inclusion, diversity and equity. For example, in an open letter to arts critics and media in 2022, Stovall called for an expansion to the concept of what makes “good” or “bad” art:

‘To be quite frank, for many, many years, theatre has been made with you, or people like most of you, in mind – the “Arts” lover who is literate in the classical theatre canon, the nuance of stagecraft, consideration of themes, use of sound and lighting, narrative frames and all the traditional makings of good theatre.

‘Now that the art form is becoming more broad, both in style and intended audience, the metrics by which we judge “good and bad” should expand as well. Consideration for community engagement, representation, authenticity in storytelling, impact for community sense of worth, self-determination and truth-telling must be factors in the “good art/bad art” question. And, in my opinion, we are not all equally equipped to discern that.’

National member-based organisations – Chloe Bonnar, Senior Relationship Manager at Pride in Diversity

Bonnar is a Senior Relationship Manager at Pride in Diversity and is leading the organisation’s foray into the performing arts. One of ACON’s Pride Inclusion Initiatives, Pride in Diversity is a national non-profit employer support program for LGBTQIA+ workplace inclusion. Any Australian workplace can sign up for either a Small (fewer than 100 staff), Standard or Principal membership depending on its number of staff and the desired level of monthly contact hours.

When live entertainment company Michael Cassel Group approached Pride in Diversity to enquire about two memberships – one for the company, and a separate membership for its musical production of & Juliet – Bonnar developed a tailored membership package.

For example, instead of evenly distributing monthly contact hours and working towards annual industry benchmarking, Bonnar concentrated her hours in pre-production and rehearsals. ‘We normally get invited in as an add-on,’ says Bonnar. ‘It’s rare that we’re invited in at the culture-building stage.’

Her focus on & Juliet was internal training and culture-building. Support from the leadership team was vital to the pilot program’s success. ‘It was really powerful to be invited in on their journey and to be given a lot of access and ability to influence some of the decision-making in policy.’

Bonnar ran her first cast training session just a few days into rehearsals. ‘The learning experience was embraced,’ recalls Bonnar. Her sessions were complemented by separate anti-racism and gender equity trainings run by other external consultants. ‘They built a culture together of this powerful, open, challenging at times, conversation with space for different perspectives. There was such a want for it to be right.’

For example, members of the & Juliet company collaborated on a Statement of Principles – encompassing commitments to education, correct pronoun use, ongoing training, understanding of language and anti-racism – that was signed by every team member, including cast and crew. The statement was backed up with face-to-face learning and an e-learning module.

Later in the process, Bonnar facilitated conversations around the policy decision to display pronouns in the cast list and program, and worked with the cast to celebrate days of significance for the LGBTQIA+ community. For example, the team d held a special performance on Trans Day of Visibility for trans and gender diverse people that invited audience members onto the stage. ‘It was all so intentional,’ says Bonnar. ‘We understand that there are visible members of this community… How do we make things better for our people who are going through a hard time?’

In-house experts – Wanyike Mshila, Community Engagement Manager at Sydney Opera House

Mshila joined the Sydney Opera House in 2022 in the newly created role of Community Engagement Manager. Her community engagement practice evolved in informal settings and community halls, and was guided by instinct. ‘I was doing what I knew what to do. It’s what I’d been doing in my community for a long time.’

A Kenya-born interdisciplinary artist, Mshila’s creative practice has taken many forms over the years, including through dance, choreography, writing, fashion design, styling and currently as a Community Engagement Manager.

Mshila has her own business, Wa-Nyika, and co-runs 2 Sydney Stylists. Under these two brands and drawing on her background in the corporate banking world and entrepreneurship, Mshila has become a specialist in designing and delivering strategies and processes that build deep, long-standing relationships between arts and cultural organisations and the communities they serve for mutual benefit.

Joining the Opera House presented an opportunity to work within a structure and reflect more strategically on frameworks, and impact evaluation and language. Mshila spent her first eight months in the role with as much time in the community as possible. She distributed as many complimentary tickets as possible to get community members through the doors, while listening, identifying patterns and, eventually, developing a considered framework that feels authentic and responsive. ‘It’s messy work,’ notes Mshila, ‘but I always bring it back to basics.’

Key advice for arts organisations

- Determine your intentions: Be clear and specific, ask yourself: who is your community? Is your goal audience development or community engagement? What does long-term engagement, outside of programming, mean to your organisation? ‘Think hard about your intention,’ urges Mshila. ‘Once you think [your engagement strategy] through – and pay attention to cultural safety and getting the right people in the room – it becomes authentic and more than transactional.’ Ensure that your team are prepared to be flexible, get things wrong and release preconceived notions.

- Lay the groundwork: Community engagement work should begin before programming. If you are programming a show for a specific community as a one-off, how will you remain connected with this community? What can you offer?

- Invest: Treat community engagement consultants as experts and remunerate them accordingly (if your funds are strictly limited, start with complimentary tickets). ‘People underestimate the amount of time and money it will take,’ says Mshila.

- Assume the best: Approach a situation assuming that everyone is doing the best that they can. This attitude ‘allows me to leave space to offer grace for the humanity that each of us brings,’ says Stovall. ‘Everyone approaches things with their own personal background and perspective, and so assuming the best in each other allows us to assume that we individually are doing the best we can, and that our work together is about how we make that a collective better.’

- Diversify your workforce: To diversify audiences, it is necessary to diversify the backgrounds of staff and artists.

- Listen: Always start with consultation and refrain from relying on assumptions. Trust that your community knows best. ‘They know what they want, they know what you need,’ advises Mshila. Build a relationship of trust and listen authentically. This will ensure that ‘information and learning [goes] back and forth, reducing the risk of things going wrong’.

- Remember that no one speaks for everyone: Community engagement consultants draw on their expertise and personal lived experience to advise on frameworks and strategies. However, Mshila and Bonnar both stress that they do not speak for everyone. Keep intersectionality front of mind and continue to ask yourself: “Which voices are missing from this conversation?”

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.