By Samuel Beckett

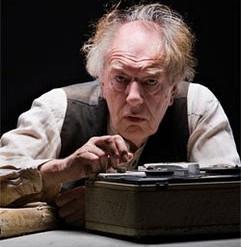

Starring Michael Gambon

Directed by Michael Colgan

At The Duchess Theatre

Philip Larkin once wrote, “Deprivation is to me what daffodils were to Wordsworth”. In Krapp’s Last Tape, Samuel Beckett’s most famous one-man play, deprivation is a veritable bouquet.

The action of the play is simple enough: on his sixty-ninth birthday, as is his custom, Krapp reviews a tape recording of one of his previous years, on this occasion digging out a reel from his thirty-ninth. However, beneath its deceptively superficial exterior the play is the most poignant of Beckett’s oeuvre – full of autobiographical allusions – and a complex and cathartic treatise on the relationship of memory to self and the (quite literal) cyclical nature of existence; stressed by the endless reels of tape and the sporadic outbursts of ‘spooool’ from its lonely protagonist (backwards, of course, we get ‘loooops’).

Krapps from the past have included John Hurt and the late Harold Pinter, so perhaps it is not surprising to see Michael Gambon – the West End’s most cherished star – in a sudden return to form under Michael Colgan’s new direction. No stranger to Beckett, Gambon had shone in a 2004 production of Endgame, performing alongside Lee Evans in a retrospectively unpredictable double act at the Albery theatre.

Gambon’s portrayal of Krapp is equally, if not more refined and well-observed. First performed in 1958 when tape-recorders were a relatively unseen technological device (Beckett even consulted a manual when drafting the play), it is ironically appropriate that half a century later they seem absurdly archaic.

Gambon’s relationship with the machine (arguably the other ‘character’ in the play) is almost perfect and there is something mechanic about Gambon’s depiction of Krapp too: as the curtain rises he is suddenly galvanised into life, as if resurrected before our very eyes just to relive a few fragments of his past. Colgan’s direction comes complete with a new banana trick which sees Krapp avoiding the all-too-obvious slip in the original script but Beckett veterans will perhaps be pleased to note that this is suitably replaced by a fair amount of phallic gesticulation. As usual with Beckett plays, the cautious laughter from the audience is almost as painful as the action onstage. I think that’s a fair indication of a successful adaptation.

Gambon’s voice as the Krapp from three decades ago reveals the suspicious optimism of youth which undercuts Beckett’s work, but the older Krapp is more assertive and sure of what he has, or rather hasn’t, achieved.

The intimacy of the Duchess Theatre and the stark, minimalist set design brilliantly capture the essence of the work. At various points Gambon is seen counting the rungs in the edge of the desk, guiding the near-sighted Krapp around his only obstacle. The space of the theatre is a fitting venue for a play which is, after all, deeply intimate and moving. If you listen closely, you can even hear the soft undulation of the waves as Krapp recalls his time spent with a past lover ashore: ‘We lay there without moving. But under us all moved, and moved us, gently, up and down, and from side to side.’

Bookings until November 20th 2010.