Daisy & Woolf invites us to reflect on the relationships between writers and canonical texts, between women writers and their literary foremothers, and more importantly, between women writers of colour and white literary feminist models.

In their influential book on 19th-century women’s writing, The Madwoman in the Attic, published in 1979, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar criticise Harold Bloom’s approach to literary genealogy. Bloom claims that a writer experiences what he calls ‘anxiety of influence,’ or the fear that he cannot free his creation from the works of the previous writers. He argues that only through a battle against literary predecessors can a writer justify the validity of his writing. Gilbert and Gubar describe Bloom’s approach as ‘intensely (even exclusively) male, and necessarily patriarchal’ because he defines the connection between writers as a battleground between fathers and sons through a Freudian prism.

Women writers were often marginalised and erased from history, especially in the time when Gilbert and Gubar published their book. Since only a few women were included in the literary canons, how does a woman writer fit into this masculine model of literary genealogy? Gilbert and Gubar ask, ‘Does she want to annihilate a “forefather” or a “foremother”? What if she can find no models, no precursors?’1

By 2022 there have been more texts that pay homage to Virginia Woolf and acknowledge her influence in both literature and feminism, including popular media articles with titles such as ‘Why Virginia Woolf Should be Your Feminist Role Model.‘ The dynamics are more complicated as we delve into the relationship between women writers of colour and white feminist literary foremothers.

Michelle Cahill’s protagonist, a writer of mixed ancestry named Mina, admires Virginia Woolf as ‘a site of experimentation and cultural questioning, subverting the idea of what self is, the gender binary and patriarchy’. The ties between women of colour and white women writers are not new, but they need a closer examination. A recent novel by Michelle de Kretser, Scary Monsters, also features an intelligent brown protagonist who perceives Simone de Beauvoir as her ultimate feminist model.

My own literary heroines have grown to include black woman writer Toni Morrison, Latina feminist Gloria Anzaldua, and Indonesian feminist Marianne Katoppo, but in my early 20s, there was only one name: Mary Shelley.

Harold Bloom’s Oedipal model of anxiety of influence, in which validity is achieved by going against the literary predecessors, does not adequately represent feminist trajectory and genealogy. Women of colour do not need to respond to white literary figures to seek validation. I share Cahill’s questions implied in her novel: How do we engage with the colonial knowledge produced by women writers we admire? How do we honour their contribution while interrogating what they erase?

Daisy & Woolf is a critical yet playful dialogue between women writers of colour – Mina the protagonist and Michelle Cahill the novelist – and Virginia Woolf, the admired writer and feminist who has marginalised a woman of colour, Daisy Simmons, in her novel. In Mrs Dalloway (1925), Daisy is the Anglo-Indian love interest of Peter Walsh, a former lover of Clarissa Dalloway. Daisy’s character is simply a sketch, inconsequential, and described as ‘pretty and dark’. Mina attempts to reconstruct and reanimate Daisy through her novel.

Foregrounding the experience of a woman of colour excluded by a white woman author, Daisy & Woolf has been compared to Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea, is a revision of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre that gives a voice to Bertha, the figure known merely as the madwoman in the attic. Rhys, like Daisy and Cahill oscillated between different cultures and was continuously subjected to unwanted curious gazes as a result of her mixed origin.

Read: Book review: Telltale, Carmel Bird

In Daisy & Woolf, Mina notes, ‘Woolf champions white women, she argues brilliantly against their subjection in A Room of One’s Own and in Three Guineas, but she uses her genius to slay Daisy Simmons’. Mina expresses her criticism towards Woolf – and she has all the right to be angry – yet she also ponders many difficult questions that reveal the complexity of the relationship between writers.

She asks: ‘Am I with Virginia Woolf or am I against her? Her repertoire of choices cast from privilege is bound to exceed mine, and yet I think I am more on her side. It is, ultimately not who I am but what I do as a writer that matters’.

The question of taking a side, whether we are with our literary foremothers or against them, does not lead to a clear-cut answer. Rather, it opens up the space for conversations around difference, power, and exclusion.

Daisy’s story mirrors Mina’s in many ways, including in her experience of loss, relationships, and travel. In Three Guineas Virginia Woolf writes, ‘As a woman I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman my country is the whole world.’ What does it mean to reclaim Woolf’s statements from a perspective of a brown woman?

In Daisy & Woolf, we are invited to rich, vivid details of clothing, food, and customs in India, where Daisy lives as a young mother of two children, but both Daisy and Mina are also cosmopolitan travellers. Daisy in 1924 travels by sea to Europe and takes notes of the places she visits along the way, and Mina, in 2017, travels from Australia to England, India, and China.

Daisy and Mina are citizens of the world who leave their footprints by navigating through borders, prejudice, and racism, both subtle and overt. This can be seen in, for instance, Daisy’s experience applying for a passport. The interviewer measured her and concluded that her skin colour is too dark.

Both Daisy and Mina are observers and flaneurs – even though it is not always easy for them to roam in public places as they are racially and sexually marked. In Mrs Dalloway, Daisy has no thoughts of her own, but in Daisy & Woolf, she observes cities and people as she reflects on her personal journey and desires. She shares her thoughts through her writing: ‘My heart pulsed tenderly for all the poor in this city; those who camp in makeshift dwellings along the railway, the women especially, who labour barefoot and wear the same gaudy saree’.

Daisy & Woolf not only brings us stories of brave, clever women in an eloquent way; it also leaves questions for us readers to think of our own trajectory of reading and influences. How do we relate to our readings and the authors we admire? How do we deal with their inconsistencies and contradictions, with what they ignore and erase? And as we honour them by responding to their work and creating something out of it, which texts do we leave out? Whose voices are we not hearing?

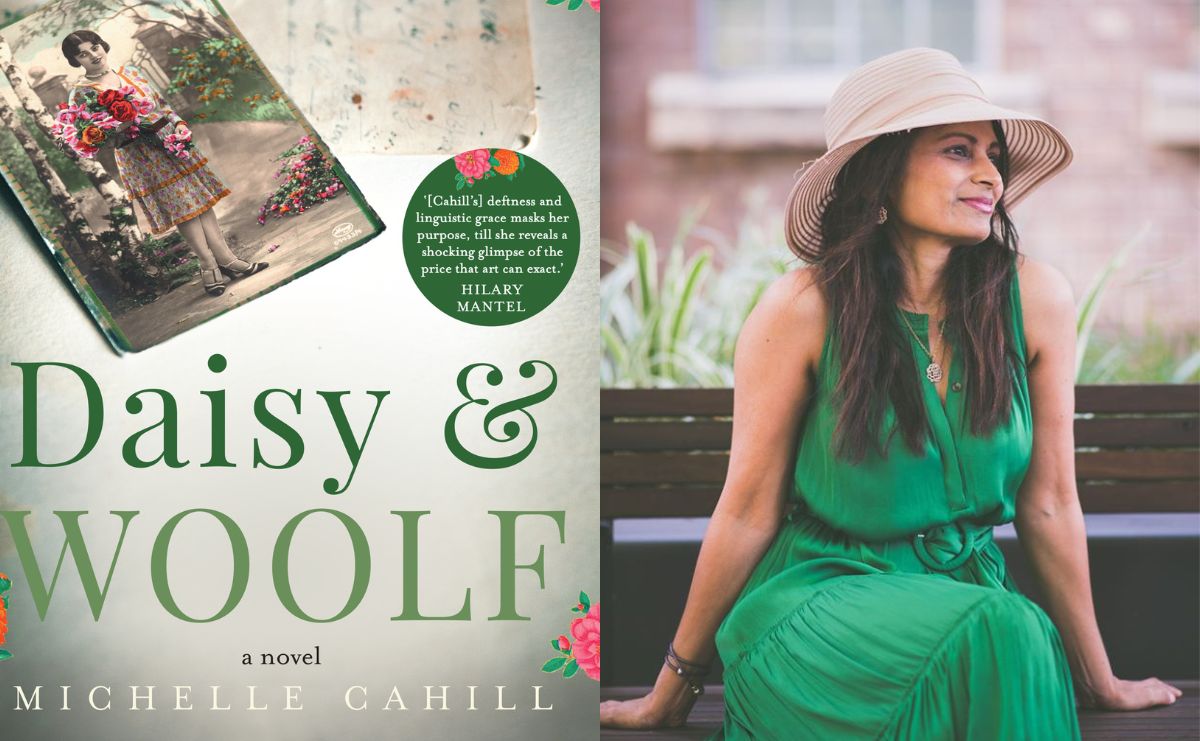

Daisy & Woolf by Michelle Cahill

Publisher: Hachette

ISBN: 9780733645211

Publication Date: April 2022

RRP: $32.99 / £14.99

Cited

1. Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), p. 22