It’s no secret that while many adults turned to books to pass the time during COVID-related lockdowns, children’s reading habits suffered when their schools were shut and, without their teachers’ encouragement, they lagged behind when it came to picking up books for pleasure.

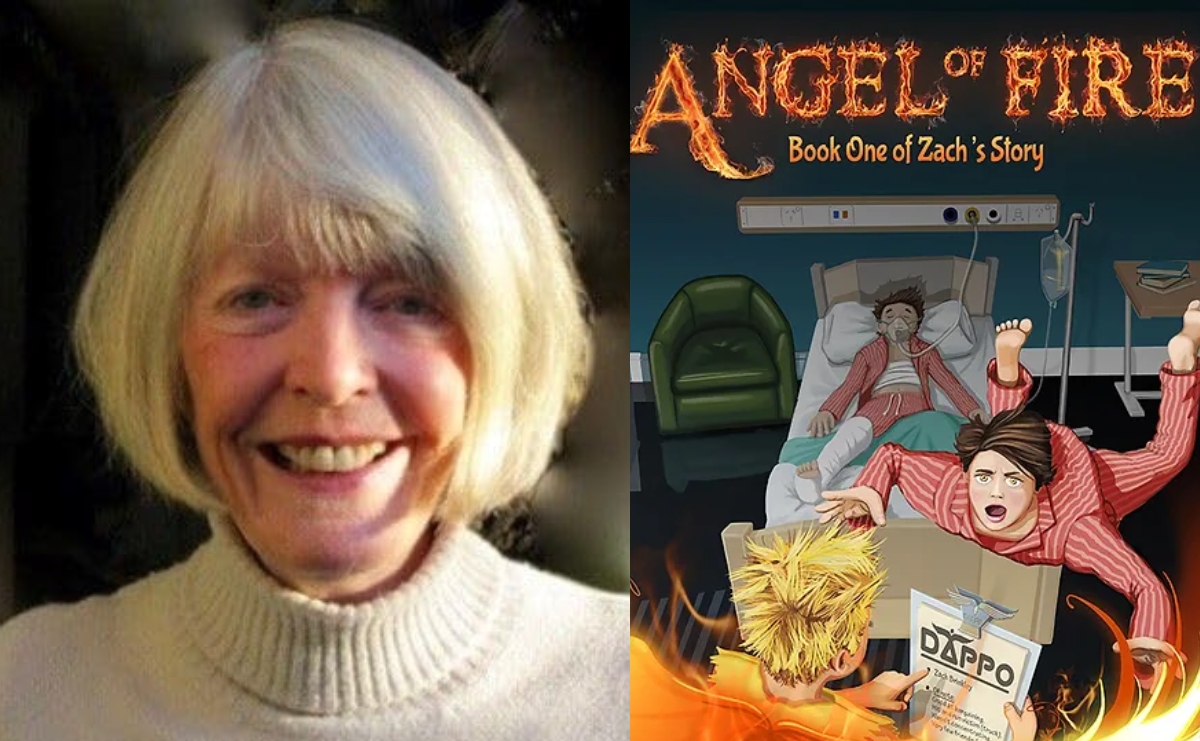

But according to children’s author Wendy Milton, creator of the Zach’s Story series (for 8- to 12-year-olds), books help with not only literacy and comprehension, but also with perseverance. ‘The best books for building resilience are adventure books with storylines that involve the characters having to solve mysteries,’ Milton says.

‘They not only get the imagination going, but they also help build courage and adaptive thinking. Children learn that not every attempt works and that they may have to come up with other ideas and approaches.’

Milton defines resilience as the ability to bounce back during or after difficult times, or the ability to keep thriving in spite of circumstances that cannot be changed. Resilient people, she says, learn from difficult situations. ‘Reading adventure books and taking part in exciting campaigns with captivating plot twists can strengthen a child’s ability to deal with setbacks.’

Learned experiences through reading

Milton maintains that the best thing parents can do is buy their children books – physical books, ideally –that can be shared around the family and also used for family reading sessions.

‘It’s important for children to learn that we don’t always win and that, even though we try, we don’t always get the result we want. That’s OK, and it can lead to even better and bigger opportunities. The key is to learn from the experience and to keep trying. This is what happens in most adventure books,’ she adds.

‘Children need to be taught, from an early age, to love books, which involves reading to them even before they can read themselves. Bedtime stories were once a part of most children’s development but, sadly, they’re more likely now to be left to their own devices (forgive the pun).

‘As a teacher I was often asked by parents how their children could improve their English. “Does [he or she] like to read?” I’d ask. Whenever the child’s English results were poor, the answer was inevitably “no”.’

Children are learning as they read, but getting them to read if they haven’t been encouraged to do so from an early age, is difficult. Bribery? It’s difficult to know how, from a national marketing perspective, we can make books “cooler” than the current devices. Perhaps parents and guardians can make reading a family entertainment or shared experience, where the onus isn’t entirely upon the child to “do the right thing”? Book reading should be a pleasure, not a punishment, and pleasures are better shared.

How do we get adults to read/buy more books and normalise reading as an everyday practice for children?

How does Milton think we can better market books? ‘Why are there no television advertisements stressing the pleasure of reading something that’s tactile?’ she responds.

‘In my experience, if the adult didn’t learn the pleasure of books as a child, then that pleasure won’t be passed on to his or her children. Perhaps an adult whose children are becoming exposed to the dangers of non-reading might be persuaded by well-known personalities in documentaries and TV advertisements to normalise reading within the family environment, to buy more books and share those books with their children.’

As for the direct correlation between books and literacy Milton points out, ‘While reading, children are learning subliminally – that is, picking up vocabulary, sentence structure, grammar, spelling and punctuation. They’re also stimulating their imaginations and many are encouraged, if they enjoy reading, to write their own stories. Reading does more for a child’s English ability than any teacher.’

Read: Sally Rippin is the Australian Children’s Laureate 2024-25

So even if school’s out? Helping children and young people reach for a book will make a difference to not just their resilience levels, but also their linguistic and learning abilities.

Wendy Milton is an Australian writer who has published 12 children’s books. The most popular is her five-book series, Zach’s Story. She’s also written one adult whodunnit, Schooled in Death, which is set in 1970s Australia.