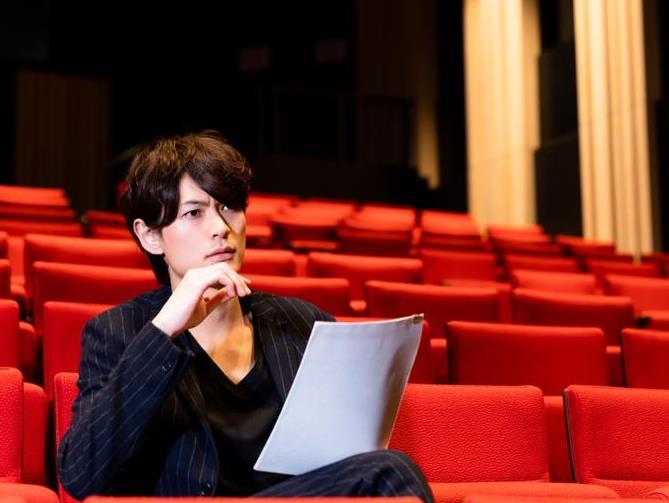

Criticism in the theatre can be more patient and considered. Image Shutterstock.

As a critic, I developed an important basic principle that I always abide by and teach my students to do the same. I call it the parking lot rule. The parking lot rule dictates that when you are seeing a show, you should obey the same general rules of critique that you might use when eating a home-cooked meal as a guest in someone else’s house. While you’re in the theatre itself, you should only say glowing, positive things about the production.

This is not to say that you need to fabricate glowing positive things to say about a lacklustre performance, but it is very rare that a show has nothing to speak well of. There are so many parts that go into a finished production – at least one of them will warrant praise of some variety. Hold on to the criticism until you reach the parking lot. This fulfils several important facets of decorum, but also abides by good old-fashioned manners: you would never insult someone’s cooking while sitting at their dinner table.

The parking lot rule gives the viewer space and time to process their critique, both the negative and positive. Knee-jerk reactions like ‘I didn’t like that’ can simmer as the reviewer teases out what underlying causes led to their reaction. Additionally, it forces someone to truly think about what’s going well before hammering on what went poorly.

Defaulting to the positive encourages unpacking nuance; rather than becoming stuck on large sweeping negative impressions, the viewer is asked to instead pull out the threads that contribute to theatrical production. They are asked to see pieces of the puzzle rather than the finished product as one macrocosm.

Hold on to the criticism until you reach the parking lot. This fulfils several important facets of decorum, but also abides by good old-fashioned manners: you would never insult someone’s cooking while sitting at their dinner table.

This is a skill that takes practice. For most, especially those with minimal experience unpacking theatre, it does not come naturally. As a pedagogical practice, it also sensitises the students to elements of theatrical production: What specific choice are they reacting to? Which member of the design team made that choice? Who might have adjusted to compensate for the choice, or shifted a production element to satisfactorily accommodate it? What might a more effective choice have been? Learning the theatre is about so much more than looking at a finished product with admiration (or disgust), and the parking lot rule can help audiences better understand the cogs in the machine through experiential practice rather than rote memorisation.

From a big-picture perspective, the parking lot rule inspires critical thought (truly the key to good criticism). It’s not enough to note that something did not work. If a critic is going to go to lengths to publish, in writing, a negative critique of someone’s hard artistic labour, they should make that critique the work of careful attentiveness rather than spur-of-the-moment judgement. Each artist wants to create something great. If you want them to succeed, you need to be vigilantly aware of your own thoughts and expectations of art.

For undergrads living in the age of instant gratification and snap decision-making, the parking lot rule is a valuable tool in the arsenal of critical thinking. It teaches the amateur critic that it is not okay to dump their negative impressions on a page without digging into the ‘why’.

While feedback is important, there is feedback that is more useful and feedback that is less useful. A well-crafted critique will not only tell the audience what to expect from a piece, but will also tell the theatremakers why the critic saw it the way they did. Additionally, this kind of education helps audiences begin to think about the critiques they take in as well as those they put out.

Understanding the thought that goes into a critique is the first step towards recognising when something is a fair piece of critical prose and when something is slapdash or thoughtless. This, in turn, is the first step towards public recognition of professional criticism as worthwhile and valuable.

This piece, originally titled The First Rule of Theatre: The Parking Lot Rule by Danielle Rosvally, was first published on HowlRound Theatre Commons on 14 July 2019.