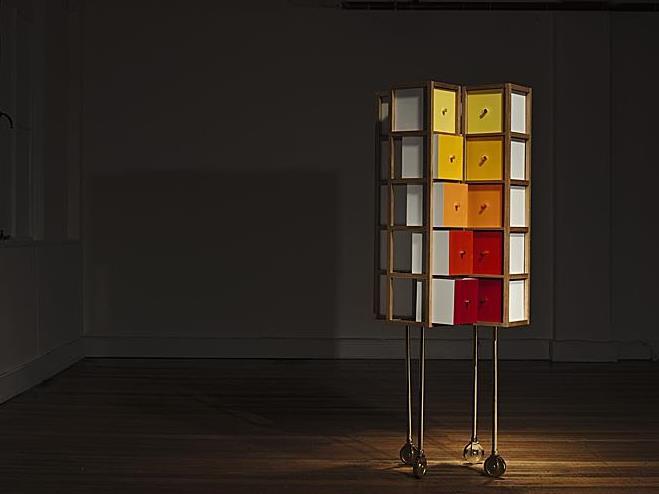

Inside Out Cabinet designed by Adam Goodrum as part of Broached East was built and painted by Emily Denton of Hawthorn Polishing and Cabinetry.

Credits deserve credit. In the cinema, the seeming endless list of acknowledgements provides an excuse to linger in our seats, adjusting back to reality. Some facts are useful to know, such as director and location. Others can be diverting, such as ‘Flash, the editing room dog’ (Brothers Keeper). But some roles are mysteries unto the film industry, such as Best Boy and Gaffer. Apart from the excuse to linger in our seats, credits help us appreciate the immense backstage team at work in producing a film.

While credits are extensive in most performing arts, the convention for product-based arts is much shallower. In visual art and design there is rarely acknowledgement of supporting specialists such as the technician, framer or printer, despite their sometimes critical role in producing the work.

Why the secrecy? The romantic concept of artist positions the creative spirit in isolation from others. On a more mundane level, the nature of industrialisation has led us to accept the production chain as an essentially anonymous process. Marketing shrink-wraps the product’s identity into a brand that says little of how it came into being.

This model is now being questioned in the arts. There is growing interest in relational practises, where art is produced collectively. The wide community collaboration involved in production of work by artists such as AI Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds, where the participation of artisans from Jingdezhen is essential to its meaning. But in commercial industry as well, there is increasing concern about opacity in supply chains, particularly after the Rana Plaza tragedy in Bangladesh.

Fashion is leading the way. New platforms are now making a virtue out of openness. Honestby provides exhaustive information about its clothes, including payment to workers, chemical treatments, and transport. On a more engaging level, the IOU Project offers consumers images of the particular Indian artisan who wove the fabric, together with the Spanish artisan who assembled it, even inviting you to upload a photo of yourself wearing it.

Australian designers are also moving towards greater openness. Deborah Emmett’s Tradition Textiles creates products for local market that are made by specialist Indian artisans: ‘In our textile business we aim to establish sustainable relationships with the talented artisans who assist us in developing our collections. As part of that process we try to include our customers by relating to them the stories behind the creation of the products.’

In product design, there is greater appreciation of the value of story. According to Lou Weis, director of Broached Commissions, ‘It’s to our advantage to be open about how our products are sourced. These are collaborative process and their story adds greatly to the value of the product. Every layer of the design outcome needs to contain a narrative that is compelling: the idea behind the piece, the design and the making all need to be rigorously and collaboratively conceived.’

This acknowledgement of contributions looms as a challenge to the way ‘moral rights’ has been understood. According to the Bern Convention, the ‘authors’ of creative works have essential rights, including that of attribution ensuring that their name remains on future reproductions. But in many creative works it is not only the artist or designer who plays a critical role, it is often also a specialist technician or craftsperson who interprets the concept drawing on their hard-earned and rare skills. Should their name appear on the label or catalogue by right?

This issue bites particularly in cases where designers are working with artisans, developing products for Western markets that carry the authenticity of a traditional object. There are often doubts about the partnership given the legacy of exploitation between first and third worlds. A Chilean designer once told me of how an artisan will no longer work with her because she was upset that she wasn’t acknowledged in the final product.

Artisans are becoming globally connected. Designers look for a point of difference and the Internet makes it easier to work at a distance. Many of the current generation of design students are keen to work in the region. The Cultural Textiles course at COFA has led to development of many successful ventures such as Walter G. As Associate Professor Liz Williamson says the course has led to ‘an engagement with Indian textile design via internships, collaborations, employment, design opportunities and further research in postgraduate programs.’ Similar pathways are offered within Griffith University’s Design Futures and Swinburne engineering.

To help overcome cultural differences, in 2006 UNESCO published Designers Meet Artisans as a guide. A code of practice is now being developed to offer standards to work by. As a contribution to this process, the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council supported development of a Code of Practice for Partnerships in Craft & Design, dealing specifically between Australia and India. Such standards promise to foster closer cultural ties, partnership by partnership.

Australia India Design Platform (code named ‘sangam’ meaning confluence in Sanskrit) has involved roundtables, workshops and forums in Australia and India over the past three years. During that time, we have found much intense debate about the nature of transparency in partnerships. While there is consensus that it is better to be open, there are some who see dangers.

In the case of labels, most agree that it is not only fair to recognise those who made the items, but it also adds value in the eyes of the user. Yet some retailers are concerned that unscrupulous customers will use this to source the product directly for a cheaper price.

Similarly, some designers are cautious in sharing information about their producers in case others will steal their hard-won loyalty.

The approach of Sangam Project is to identify standards that are agreed upon as ideal. These are grouped according to the twin principles of honesty (‘the right to know’) and respect (‘the right to be known’). Given an imperfect world, there will be many reasons why these ideals may not be followed. Essential to the code’s construction is a process of sharing advice and ideas for working around these roadblocks. For instance, in the case of retail labelling, a wary retailer might offer background information as part of a loyalty program to increase customer value.

The draft version of the code will be taken to India in December as part of a program of events exploring Australia-India design partnerships in Bangalore. Emerging from this event will be a network of artisans and designers in Australia and India who are interested to work together according to shared ethical principles. The plan is to extend this to include Indonesia next year. It also provides a model for intranational partnerships between creative developers and producers within Australia.

Before Bangalore, there is the opportunity to have a say about what is considered fair and reasonable in these creative partnerships. To view the draft code and contribute to its development, please go to www.sangam project.net/code.

A wide canvas of thoughts helps build the consensus on which new conventions are possible. As the Spanish poet Antonio Machado once wrote, ‘the road is made by walking.’