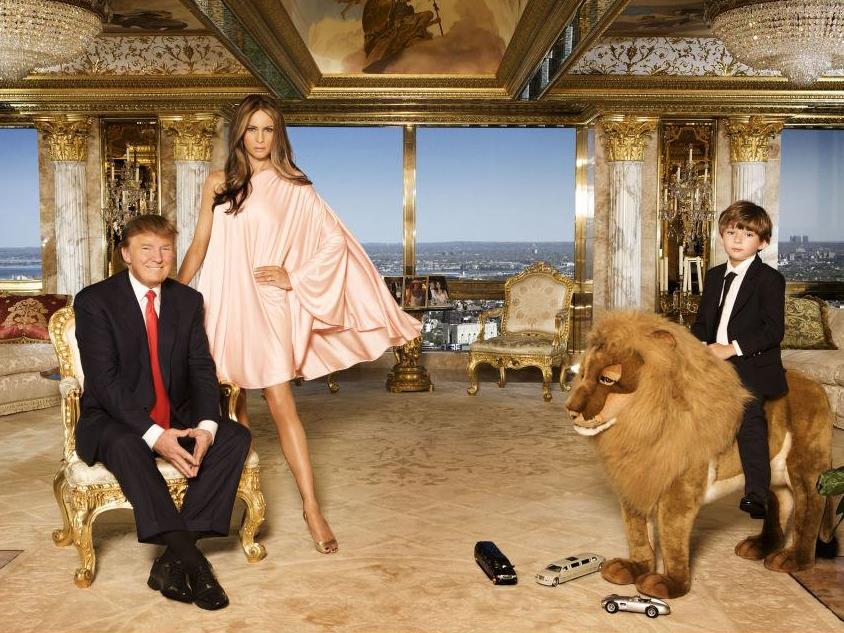

During his campaign, Donald Trump posed with wife Melania and son Barron for Home Beautiful.

Yellow-gold swagged curtains, glimpsed in the first pictures from the Trump administration’s official duties in the Oval Office, have fuelled speculation over whether America’s new president will bring his signature taste in interior design to the White House.

Striped crimson curtains and a rug with quotes attributed to former presidents installed by former President Obama, have been replaced with patterned gold drapes and a sunburst rug (reportedly designed by Laura Bush during her husband’s presidency). Framing himself with gold and sunbursts, America’s new president appears to be unperturbed by those who have compared his ostentatious style with that of The Sun King.

The media and popular bloggers have been quick to draw a link between the famous glittering décor of Trump’s Manhattan penthouse and Louis XIV’s Palace of Versailles. Kate Wagner creator of the popular satirical blog McMansion Hell, asked Whose Style is That? Louis XIV or Donald Trump?

The comparison holds at a cursory glance: the acres of marble, gilt capitals on columns, fountains and painted ceilings in the Trump triplex nod in the direction of the Sun King’s palace. But a confusion of references to interiors and furniture made over more than 130 years in the two long reigns of Louis XIV (1643–1715) and his great-grandson Louis XV (1715–1774) makes it impossible to classify this style in relation to a specific period. Trump’s apartment might, then, best be described as neo-French grand manner.

It is easy for a historian of French decorative arts to point out the errors of reference in Trump’s apartment to the designs that inspire it. The proportions are all wrong: the columns are wide and squat, the entablature above the gilt capitals too narrow, and the cornice below the painted ceiling far too wide.

Not to mention the heavily gilt Louis XV inspired armchairs (or fauteuils to use the proper term) that have none of the sinuous appeal of their 18th-century forbears. Proportion governs elegance in the palaces of the Bourbon kings, and such errors would have been considered extremely poor taste then, as they are now.

Trump is far from the first to emulate the decorative style developed for Louis XIV and his heirs. Some of the most extraordinary examples of neo-French grand manner design are found in the palaces of the reclusive Bavarian king Ludwig II (r. 1864–86).

Obsessed with old-regime France and all that it entailed, Ludwig built a replica of Versailles on an island in the Chiemsee lake, 60 kilometres south of Munich. Among his many follies, the Bavarian king employed an army of artisans to recreate the Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors at Schloss Herrenchiemsee.

Robber barons of late-19th-century America had a penchant for the decorative arts of Bourbon France too. Alva Vanderbilt, one of the most flamboyant patrons of the Gilded Age, is said to have started the fashion at William K. Vanderbilt House on Fifth Avenue, New York (called the Petit Chateau), with rooms lavishly decorated in period styles.

Alva and her peers wanted the real thing when they could get it, and imported 18th-century boiseries (carved wooden panelling) looted from crumbling French chateaux to install in their mansions and set off their superlative collections of art and furniture. Vanderbilt’s homage to the old regime was, perhaps, more successful than chez Trump, but the nod to a stately French style to show off new money serves the same purpose in both cases.

Putting questions of taste and period style aside, it is worth considering the comparisons made between Trump and Louis XIV. Trump’s opponents are keen to point to his taste as evidence of an unscrupulous and self-serving man with despotic tendencies.

Popular wisdom holds that there is a direct link between the grandiose decoration of French Royal palaces and the 1789 French Revolution; Versailles has come to represent a gilded style of tyrannical opulence for the privileged few at the cost of the many.

Scholars of Louis XIV France tell another story. Louis XIV’s enterprising minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert sought to boost the French economy by supporting luxury industries, creating new manufactories for all the things that wealthy people wanted to buy: mirrors, tapestries and furniture; silks and lace for fashionable clothes.

Heavy embargoes were placed on imports, and the French elite were forced to buy local. Versailles became a showcase for these magnificent luxury products, and it worked!

That Paris is still considered the capital of fashion, and French decorative arts still copied by Trump, and many others besides, attests to the enduring success of Colbert’s plan.

Trump’s call for a protectionist economy in America in his election campaign and inauguration speech is perhaps the closest comparison we could make between him and Louis XIV.

If he is inspired by the Sun King (and he has made no public admission to this) he would do well to look to leading contemporary artists and designers for inspiration on how to become a world leader in matters of style.

This article is drawn from a forthcoming book on Louis XIV style from the 18th to 21st centuries, and will be presented at The National Gallery of Australia conference: Enchanted Isles, Fatal Shores: Living Versailles this March.

Robert Wellington, Lecturer, Art History and Visual Culture, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.